A month ago, international public opinion was horrified by the news that Ukrainian journalist Viktoria (Vika) Roshkina had been tortured and killed in a Russian prison. The details of this disturbing crime, which emerged shortly before being returned in a prisoner exchange, confirmed once again that Russia is waging a terrorist war with no respect for international law.

The family requested DNA evidence to confirm that the disfigured face and 30 kg body, completely bruised from electric shocks and stab wounds, belonged to the 27-year-old journalist. Viktoria Roshkina disappeared in August 2023 while reporting from eastern Ukraine under Russian occupation. After her disappearance, all attempts by her family to find out anything were met with silence from the Russians. It was only after ten months that it became known that the journalist was being held in Taganrog prison in Russia. On September 19, 2024, Vika’s family was notified of the young woman’s death.

Such horrors are not uncommon in Ukrainian areas under Russian occupation. Vika Roshkina was captured while doing her job as a journalist in the Zaporizhia area and was initially detained and tortured in secret detention centers in the occupied areas before being transferred to Russia.

The Center for Civil Liberties has a Nobel Peace Prize

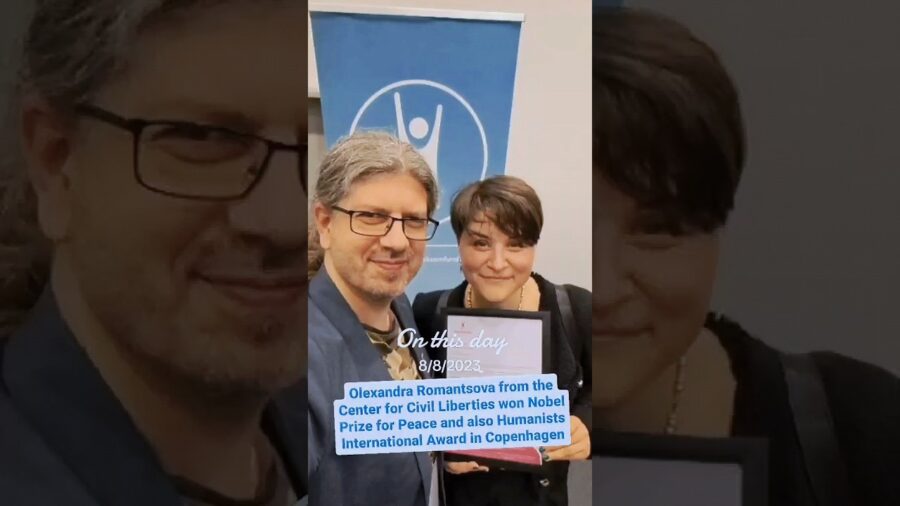

Journalists from the Association of European Journalists (AEJ) wanted to learn more about the situation of Ukrainians under Russian terror from Oleksandra (Sasha) Romantsova, executive director of the Center for Civil Liberties in Kyiv (CLC), an organization that has been monitoring the situation of Ukrainians in the occupied areas since 2014.

The Center is co-winner of the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize alongside the Memorial Foundation in Moscow. In 2023, Oleksandra Romantsova received the International Humanist Award in Copenhagen, alongside Romanian activist Remus Cernea, founder of the Solidarity for Freedom of Conscience Association.

The Center for Civil Liberties in Kyiv has been on Russia’s list of “unfriendly” organizations since 2015, so it’s not allowed in the occupied territories. Its members, collaborators, and volunteers risk their lives if they go into Russian-held areas in Donetsk, Zaporizhia, Luhansk etc.

Gian-Paolo Accardo (Italy) and Cathérine André (France) moderated Sasha Romantsova’s meeting with AEJ members on the VOXEUROP platform, which publishes articles, podcasts, and videos with the aim of animating the European public space by telling stories about Europe. The topics covered are the most pressing issues facing countries on the continent.

There is silent resistance

Although blacklisted by Russia, the Center manages to gather information about what is happening in the occupied areas through brave Ukrainians who manage to smuggle out flash drives with videos or transmit information through indirect channels. The internet and phones are useless because they can be detected, and the consequences are loss of freedom or even death. In fact, no humanitarian organization, not even the Red Cross, has been able to enter the occupied area, namely Crimea, since 2017.

Sasha Romantsova recalls a teacher from Mariupol who managed to flee to Georgia after a year and a half under occupation. With a memory stick hidden in food, she managed to return to Ukraine: “That stick contained documentation of over 2,000 crimes in the area,” says Sasha.

Even lawyers cannot enter the occupied areas to defend Ukrainians from abuse, let alone the Ukrainian or foreign press. Lawyers who are absent from the territory for six months lose their license. In any case, there is no justice and no respect for human dignity:

“If you are a journalist, religious leader, activist, or political leader, you are a target. You can be kidnapped, tortured, killed, and you will have no defense,” reports Sasha Romantsova, adding that over 20,000 children have been kidnapped and deported, about whom nothing is known. Most children and adults disappear from the Nikolaev area.

The organization’s figures show that at least 7,000 civilians have been arrested without charge, five journalists are being held captive as “traitors,” and 173 civilians have died in illegal detention. The center collaborates with the Memorial Foundation in Moscow, which is also banned, but with which it corroborates the information it obtains with great difficulty.

Because there is no independent journalism, only Russian propaganda, citizens are filling this role as best they can, when they can. There is a certain resistance, but the threats are immense. Twenty-six people have been arrested for trying to send a group letter about the abuses.

The terror is extreme: if a child says something bad about Russia at school, their parents are arrested and the child is deported, as is the case if they recite a poem in Ukrainian or take online lessons in the Ukrainian system. Sometimes it is the teachers who report them. People are forced to send their children to training camps, from which they do not know if they will ever return.

“Any connection with Ukrainian identity is considered hostile to Russia and treated as a crime or treason,” says Sasha. Ordinary citizens who own books in Ukrainian are listed as “Nazis.” You can only use Russian on the phone to avoid trouble.

27 bodies found in torture chambers

Despite all the obstacles and difficulties, the Center for Civil Liberties has managed to identify several torture chambers in villages in the occupied areas, as well as 27 bodies with horrific signs of physical torture.

“We experience the terror of Bucha every day in the occupied territories,” the activist says, providing evidence.

Witnesses recounted a terrifying episode in a village: a Russian soldier would ring the doorbell or knock on the gate and shoot whoever opened it, without warning or a word. It didn’t matter if it was a woman, a man, a child, or a grandparent. The same crime happened at six houses. It is not known whether it was a moment of madness on the part of the soldier or whether he was following orders.

“To see a village of 800 inhabitants with 50 graves in each yard is incomprehensible.” One explanation could be that the Russians do not take their dead with them, leaving them where they fell. The Ukrainians bury them for sanitary reasons, but also out of Christian compassion.

Of the 4-5 million Ukrainians remaining under Russian occupation, most are elderly people who either did not have the means to flee or did not want to leave their homes. They are used in propaganda to show that they agree with Russia’s policy and are loyal to it.

Propaganda infiltrates all channels, the internet, television, and the Russian press. “At first, around 2017-2018, a car with a large screen broadcast news exclusively from Russia circulated through the towns. After 2022, any information from and about Ukraine can only be obtained secretly, at great risk,” says Sasha.

Hybrid war on seven levels

Ukrainians under Putin’s boot have no plans for the future. They are content to stay alive or, at best, escape from hell.

“Although we and our children have to flee to shelters two or three times a day, we still have a life in Ukraine. Beyond that, in the occupied territories, there is only fear, nothing is normal,” compares Sasha Romantsova.

Humor is also a way of coping with the state of war, as demonstrated by Andrei Kurkov, a satirical writer who created an allegorical character, Viktor the penguin, with many political references. We also remember the videos made with cell phones by Ukrainian soldiers on the front lines, which contained a good dose of humor, albeit bitter.

More difficult to bear is the mind games, propaganda aimed at changing the community’s mindset, in the sense that under occupation no one has the right to their own voice.

Sasha Romantsova’s organization is monitoring Russia’s physical and cyber targets, which want to destroy the demographic and property infrastructure, as well as the energy and health systems. The latter two are more visible, but the others are just as dangerous, because Ukraine would risk no longer being able to operate its tax system or register its citizens. Identity theft is commonplace on the front lines, with Russians frequently doing this to children deported to Siberia or the Kamchatka Peninsula, whose identities are changed.

The hybrid war is therefore being waged on seven levels: economic, political, military, demographic, cyber, propaganda, and identity.

“It’s all about hatred, power, and control,” concludes Sasha Romantsova in her report to journalists from the Association of European Journalists.

Urmăriți PressHUB și pe Google News!